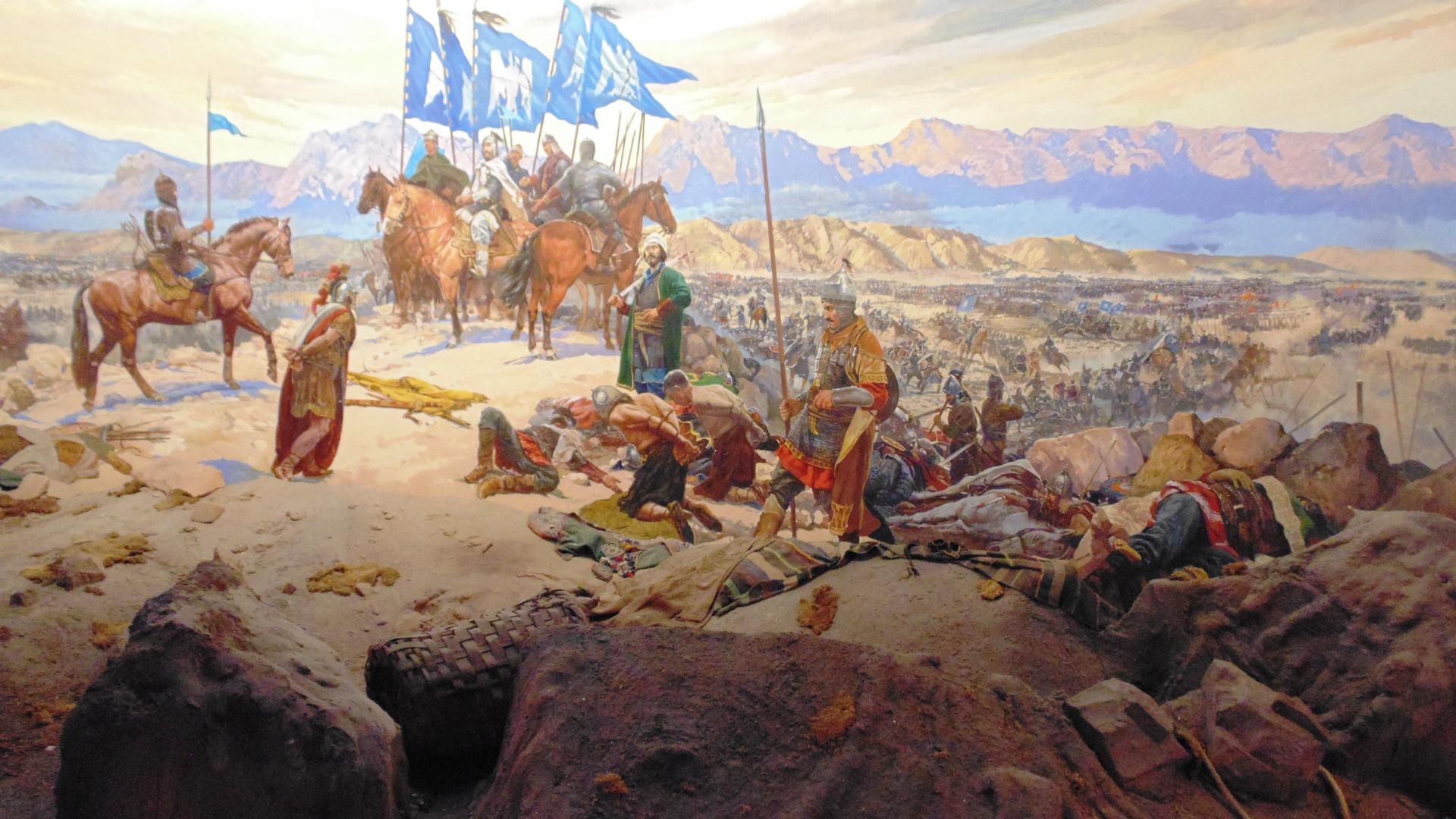

On August 26, 1071, nearly a thousand years ago, Alp Arslan, the sultan of the Muslim Turkic Seljuk dynasty, defeated a large Byzantium army led by Romanos IV Diogenes, the emperor of the Greek-led Christian empire and a great power of the time along with Europe’s Holy Roman Empire, at the Battle of Malazgirt or Manzikert.

The battle significantly altered world history, escalating the historic confrontation between the so-called Christian West and Muslim East. Following the defeat at the hands of Alp Arslan, European Christian states formed an alliance to attack Muslim lands in the Middle East, launching the disastrous Crusades in 1095.

The Crusades continued for nearly two centuries, devastating the Middle East.

With the Battle of Malazgirt, a town in today’s eastern Turkey, the Turks gained crucial access to then-Christian-majority lands of Anatolia, where the influence of Islam and Turkic culture grew gradually under successive Turkish principalities. The Great Seljuks continued gaining territory and kept marching towards Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), the capital city of the Eastern Roman Empire and European landscape.

One of these principalities, the Ottomans, who were settled into western Anatolia by the Seljuk rulers of the peninsula in the 13th century, would later go and conquer the Balkans and much of the Middle East, establishing a political and military dominance in both the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea.

“The Battle of Malazgirt is one of the most crucial incidents and a turning point in the world history,” wrote Professor Mukrimin Halil Yinanc, one of the top Turkish historians on the subject of the Seljuks, in his reference book, The History of Turkey, The Age of the Seljuks, which was republished in 2013 by the Turkish History Association.

Anatolia: the new homeland of the Turks

The victory allowed the Turkmens, which is a particular term used to describe the Muslim Turks, establish an individual state, the Anatolian branch of the Seljuks, and expand from the eastern plains of Anatolia to its western shores. The Great Seljuks were originally based in current Tehran in Iran.

Yinanc believes that the battle also paved the way for a cultural and political synthesis between Seljuk-led Muslim Turks and then-Christian-majority Anatolian populations, leading to the emergence of a powerful and well-organised Turkmen nation in the heart of the ancient peninsula.

“The battle also signifies the most important starting point of the Turkmen march and conquest across the Balkan Peninsula, Hungary, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, the whole North Africa and the Black Sea Basin, establishing the world’s greatest and the most continuous empire [the Ottoman Empire] after the Roman Empire,” Yinanc opines.

But the battle also carries a particular importance for the Islamic history beyond the battle’s implications and results of the Turkish history, according to many experts including Yinanc and his western colleagues.

The Seljuk takeover of Anatolia should be regarded as one of the most remarkable developments of Middle East history, writes Andrew Peacock, a professor of history at the University of St. Andrews, in his book, Early Seljuq History, A New Interpretation.

Peacock notes that the Byzantium Empire, which won back-to-back victories against both the Sasanids, a powerful Persian-led dynasty across Iran and Central Asia, and Muslim Arabs [after some initial failures], had been soundly defeated by the Turks in ten years between 1071 and 1081, only being able to hold a few ports across Anatolian coasts.

A Muslim victory

“Old Islamic historians had regarded the victory [at the Battle of Malazgirt], which opened the Anatolian lands to Muslim migrations, in equal terms with the Battles of Yarmouk and al-Qadisiyyah, which also laid ground for the victory of the Muslims in the Asian and Mediterranean territories [in the 7th century],” writes Yinanc.

The Battle of Yarmouk, which was won by the army of Rashidun Caliphate against the Eastern Roman Empire forces in 636, signified the beginning of the collapse of the Byzantium rule in the Middle East, primarily in Syria and Palestine.

With the Battle of al Qadisiyyah, which fatefully happened in the same year as the Battle of Yarmouk, four years after Prophet Muhammed’s death, the Muslim forces defeated a large army of the Sassanid Empire.

Both battles signify unexpected decisive Muslim victories against the then-existing super powers of the world, the Romans and the Sassanids.

The Turkish victory at the Battle of Malazgirt had also somewhat been unexpected by the arrogant leadership of the Byzantium Empire, which refused to make peace with the Seljuks while Alp Arslan reportedly sent his envoys to sue for peace.

Almost a century later, the scenario was repeated as the peace offer from Anatolian Seljuk leader, Kilij Arslan II, was rejected by the Byzantium leadership. In 1176, at the Battle of Myriokephalon, another Byzantium army was destroyed by the Seljuks, ending all dreams of expelling the Turks from the Anatolian landscape.

The sophisticated Byzantium Empire, which was a synthesis of ancient Greek culture and Roman political wisdom, thought that if nomadic Turks (the Seljuks in this case) sued for peace, it meant they were weak and they should have been run over accordingly.

But Alp Arslan, arguably one of the best Turkish generals across Turkish history, and a man with the will power of steel, was also no sitting target at all.

Before facing Diogenes’s army directly at the Battle of Malazgirt, Alp Arslan and his highly mobile and charismatic commanders masterfully penetrated the Anatolian heartland of the Byzantium, harassing the empire’s regional castles and military posts incessantly.

Ahead of Malazgirt, Alp Arslan also weakened the two main regional Christian allies of the Byzantium Empire, Armenians and Georgians, in consecutive battles in Caucasia and eastern Anatolia, allying with the Marwanids, a Muslim Kurdish dynasty at the time.

The Marwanids had provided at least 10,000 volunteers to Alp Arslan’s army according to both Yinanc and Osman Turan, another prominent Turkish historian on the history of the Seljuks, indicating the early signs of historic Turkish-Kurdish alliance against the Byzantium Empire and other powers.

The location of the battle was also not coincidental at all.

Malazgirt, currently a district in Turkey’s eastern province of Mus, is close to Ahlat, a strategic town northwest of Lake Van in eastern Anatolia, and had been the western military headquarters of Alp Arslan’s raiding commanders for years.

Diogenes and his generals strongly thought that in order to eliminate the Turkish threat in Anatolia, they needed to destroy the Turkish military establishment in Ahlat and eastern Anatolia. As a result, Diogenes marched from Constantinople to Ahlat and Malazgirt to face the Seljuk army with a luxurious convoy.

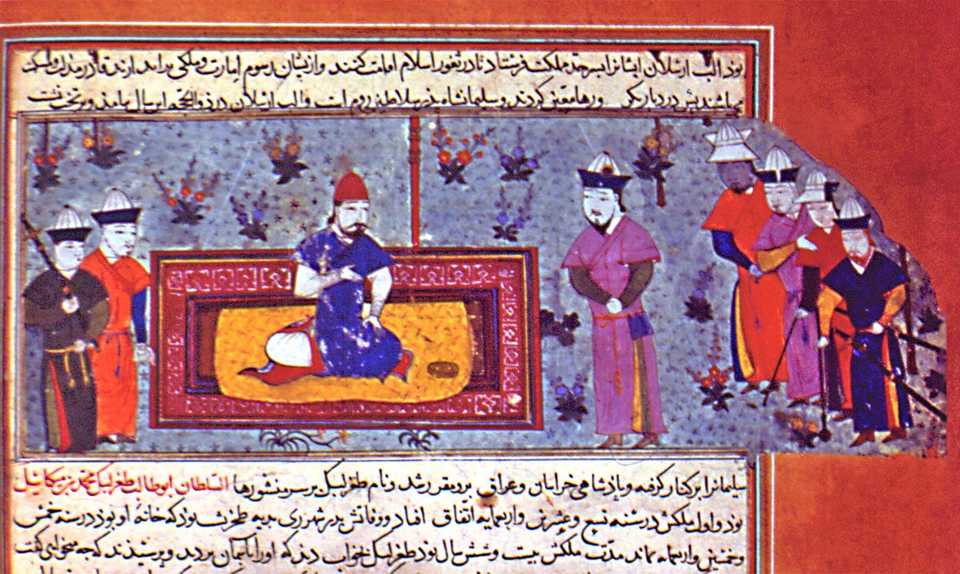

On the other hand, Alp Arslan, both a simple nomadic military leader and a smart politician, who deployed into his service Nizam al-Mulk, a leading Sunni Muslim Persian political thinker, as his grand vizier, marched back from Damascus leaving his Syria campaign aside towards Ahlat, understanding that the battle might have been inevitable.

Before it, the Sunni Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad sent a prayer for the victory of Alp Arslan to be read in mosques across the Islamic world, according to both Turan and Yinanc.

“Oh Allah! Raise the flags of Islam and do not leave your mujahiden, who do not mind to sacrifice their lives to follow your rule, alone. Make Alp Arslan victorious over his enemies and support his soldiers with your angels,” the prayer said, according to Turan.

While there were different claims about the size of both armies, there is almost a consensus that the Byzantium army was twice as large as the Seljuk army, having French, German, Norman and Scandinavian mercenaries alongside its main force.

Right before battle commenced, Alp Arslan advised his army in a public speech to nominate his son, Malik Shah I, as the next sultan of the Seljuks to prevent political chaos in the case of his death at the battle, wearing a white cloth, which suggested that he was seeing his death as a possibility.

“Oh my soldiers! If I became a martyr, this white cloth should be my shroud,” he said.

But against all expectations of both Roman Diogenes and Alp Arslan, the battle ended with a decisive victory for the Turks.

In an exceptional historic incident, even the emperor was imprisoned by Turkish forces.

The victory was enthusiastically celebrated across the Islamic world, including Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, according to Turan, the Turkish historian.

“The whole city of Baghdad was decorated as unseen for decades, building ‘triumphal arches’. Music was played as people hit the streets of the city to celebrate the victory,” Turan wrote in his book, The History of Seljuks and The Turkish-Islamic Civilisation.

“As a result, the magnificent victory, which came into existence with the imprisonment of a Byzantium emperor as a first in history, has been celebrated in accordance with its significance.”

Discussion about this post